Three dead bodies. One half-dead man. Three red herrings. And one hatchet.

Three dead bodies. One half-dead man. Three red herrings. And one hatchet.

On January 15, 1944, Arthur Decker Brown stumbled into the Rainbow Tavern on East Sprague Street in Spokane, Washington. The bartender recognized him as an employee of the sign-painting shop next door owned by T. P. Dillon and his wife, Flora Gertrude Dillon. He offered him a beer, but Brown seemed dazed and did not reply. When Brown finally found his voice, he rasped “Go next door-around the back-see if you saw what I saw. It’s a massacre at the Dillons’.” The bartender knew that the Dillons and some others had been partying the night before at the Rainbow. When the bar closed at midnight, the revelers bought beer and continued the merriment next door at their place. The barkeeper did as Brown told him, entering the small apartment the Dillons lived in behind their sign shop. Then he returned to the Rainbow and called law enforcement.

Four blood-covered corpses awaited the police upon their arrival at the crime scene. Three were on the bed. Looking more closely, the police found that two of the bodies still had pulses; they were rushed immediately to the hospital. The survivors were a young woman in her twenties named Jane Staples and a man named Frank Stanish Winnett. Staples died soon after from her horrific hatchet wounds but Winnett survived despite sustaining nine skull fractures. The Dillons were already dead when the police arrived on the scene. The coroner determined that they had expired around 5:00 am on the morning of the 15th and that they had eaten a breakfast of bacon and eggs approximately one half-hour before.

The police discovered a bloody hatchet about 15 feet from the back entrance to the Dillons’ apartment. The brand was True Temper Tomahawk and it had the initials “PD” carved into its wooden handle, perhaps for “P. Dillon.” Suspicion fell first on Brown, who not only had reported the crime, but had been fired the day before from his job at the same sign-painting shop. Then a man named Edward Quentin became a person of interest because Winnett had been muttering “Ed Quentin” as he was being transported to the hospital. Quentin himself showed up at the prosecutor’s office soon afterward and declared that though he and the survivor worked at the same plant, he had no connection to the crime. The fifty-five-year-old husband of Jane Staples next came under suspicion, since his shoes had blood on them, and because he knew that his wife had cheated on him with at least three other men. In his defense he claimed that the blood had come from a nosebleed.

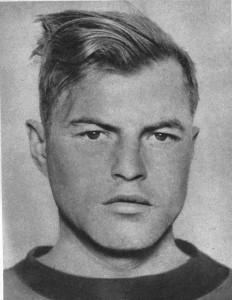

Finally, the police turned a jaundiced eye on Woodrow Wilson (“Whitey”) Clark, 30, a drifter from Maine who had been drinking with the Dillons that night. Two newspaper delivery boys for the Spokesman-Review picked Clark out of a lineup as the man they had seen early that morning wearing a bloodied sweatshirt. Upon interrogation, Clark revealed that he had used the hatchet to chop wood for the stove in the Dillons’ kitchen so that he could fix them a breakfast of bacon and eggs. He said he left them at about 2:30 am, after cooking the meal and well before the party ended. This time frame conflicted with the forensic and eyewitness evidence and the police arrested Clark, charging him with murder.

Jurors decided that the massacre had been sparked by Clark’s advances toward one of the dead women. He was hanged at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla on February 4, 1946.

Back to Crime Library

|

|

|